The T-shirt is at once the most ordinary and the most extraordinary garment in human history. Born of necessity and simplicity, it has traversed oceans and eras, worn by blue-collar workers, seafaring sailors, Hollywood stars, street-corner poets and stadium crowds alike. Yet within its humble knitted cotton folds lie stories of innovation, rebellion, artistry and global commerce—stories that together trace a thread through the last century of social change, technological progress and creative expression.

Imagine the turn of the twentieth century: a heavy, one-piece union suit, its stiff wool or cotton fibers covering soldier and civilian alike, proving both cumbersome to wash and sweltering in summer months. As the seams at the torso were clipped and cut away, the upper half—the first true prototype of our modern T-shirt—emerged. It was adopted promptly by the U.S. Navy during the First World War as an undergarment that was quick-drying, easily laundered on ships, and provided a comfortable barrier under woolen uniforms. Returning veterans, accustomed to the garment’s cool comfort, peeled off their regulation shirts and wore their T-shirts alone; thus began the gradual migration of this piece from the laundry room to the street.

In the 1920s and ’30s, department stores began to stock simple, collarless cotton shirts marketed as “undershirts,” sold in unremarkable white. Little more than a functional layer, the T-shirt remained invisible beneath button-downs. But by the 1940s, fashion and utility converged: the Second World War once again normalized T-shirts as standard-issue undergarments, and postwar realities—economic shifts, a burgeoning leisure culture—encouraged casual dress. Suddenly, the white crew neck became not just underwear but a standalone top.

Then Hollywood discovered it. In 1951, Marlon Brando appeared shirtless save for a form-fitting T-shirt in “A Streetcar Named Desire,” his raw masculinity and the garment’s stark simplicity rippling across the silver screen. Four years later, James Dean, standing in the glare of neon in “Rebel Without a Cause,” held his jacket slung over one shoulder to reveal a cigarette-smoking outlaw dressed in a plain white tee—a uniform of teenage angst, defiance, and cool indifference. Across America, young men and women reached into their drawers for the same blank canvas, eager to emulate that effortless, rebel-without-a-cause swagger.

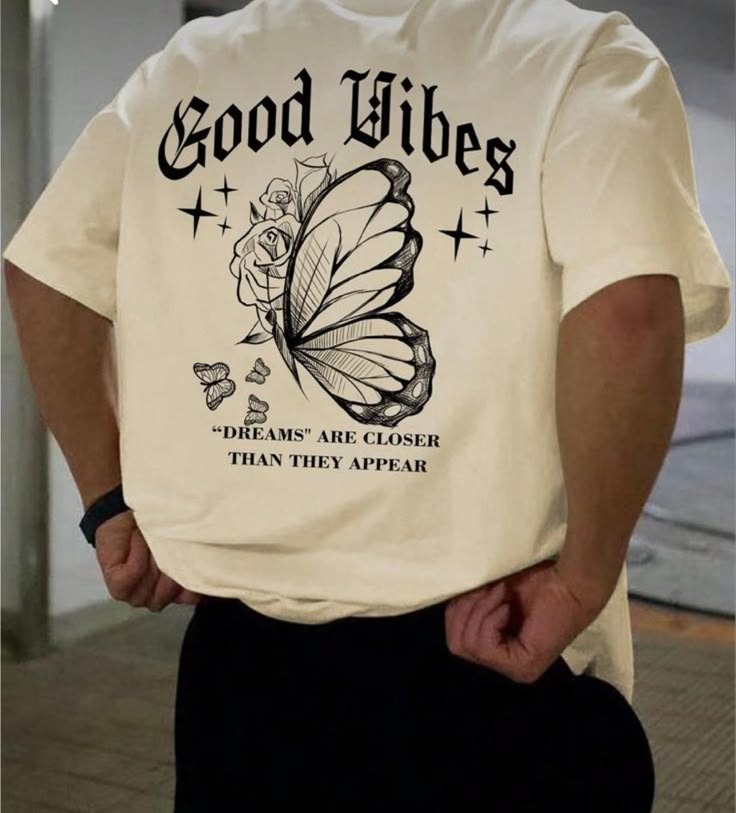

The 1960s carried that transformation further: the T-shirt evolved into a political billboard and a musical identity. Civil rights marchers printed “I Am a Man” across their chests; anti-war protesters emblazoned peace signs and slogans on their cotton fronts; musicians of every stripe, from The Beatles to Jimi Hendrix, turned tees into moving fan art. The invention of the silk-screening process democratized design, shifting T-shirt production from the factory floor to dorm room worktables. Countercultural artists and grassroots movements used hand-paint, block print, and tie-dye to personalize each shirt—each garment an emblem of individual creativity and communal sentiment.

By the 1970s and ’80s, subcultures carved out identities through T-shirt iconography. Punk rockers appropriated shredded tees and anarchic slogans; skateboarders flaunted bold graphics and underground logos; early hip-hop collectives used bright, oversized shirts to assert urban identity. At the same time, global corporations recognized the T-shirt’s power as a low-cost, high-visibility marketing tool. Promotional giveaways, concert merch booths and big-box store racks filled with branded tees turned the garment into the world’s most prolific billboard.

Underneath every printed graphic or embroidered patch, however, lies a foundation of fabrics and fiber science. The classic T-shirt is constructed from single-jersey knit cotton. This fabric breathes, stretches, and feels soft against the skin, qualities born from cotton’s natural properties and the looped knit structure that grants elasticity without added spandex. In the 1970s, polyester blends arrived—cotton-polyester withered less in the wash and resisted wrinkles; tri-blends introduced rayon to deliver drape and softness; eventually, bamboo and modal fibers promised a greener footprint and moisture-wicking performance. Outdoor and performance brands experimented with Merino wool, lauded for thermoregulation and odor resistance, transforming the T-shirt from a casual staple to a technical layer in active wardrobes.

In garment factories across Asia, South America and Eastern Europe, T-shirts tumble through dye vats and heat presses in massive batches. The fabric’s weight—measured in grams per square meter—determines its application: 120–140 GSM cotton feels light and airy, perfect for tropical climates or layering; 180–220 GSM pique knit brings body and opacity, shaping polo shirts and textured polos. Each shirt’s pattern must be drafted with precision: shoulder seams aligned to the human slope, armholes cut to allow motion without gape, neck openings that sit neither too tight nor too loose. Advances in digital pattern-making and 3D body scans portend a future in which made-to-measure tees may be knitted on demand, virtually eliminating fit-based returns and reducing waste.

Yet, for all its ubiquity, the T-shirt is at the center of profound ethical and ecological questions. Cotton, the world’s most popular natural fiber, demands prodigious water—nearly 2,700 liters to produce the cotton needed for a single T-shirt—and heavy pesticide use in non-organic fields. Synthetic polyester, derived from petroleum, sheds microplastics with each wash, infiltrating rivers and oceans. Dyeing and finishing processes often employ toxic chemicals, leaching into waterways and endangering ecosystems. Meanwhile, fast-fashion’s breakneck production schedules drive labor practices toward the lowest possible wages and corners cut in factory safety. The casual simplicity we admire on the street often conceals long hours, low pay and hazardous conditions in far-flung workshops.

In response, a growing vanguard of brands, activists and innovators is challenging the status quo. Organic cotton, grown without synthetic pesticides or fertilizers, cuts chemical runoff but still requires water; regenerative agriculture, which restores soil health and captures carbon, promises a two-pronged environmental benefit. Recycled polyester, spun from post-consumer plastic bottles, reduces reliance on fossil fuels, though it does nothing to stem microplastic pollution unless paired with advanced washing filters. Tech startups are exploring fabrics from algae, mycelium, and even insect-derived silk, pushing the boundaries of what a T-shirt can mean in a circular economy.

These material revolutions coincide with new business models. Clothing-rental platforms allow subscribers to rotate through curated tees rather than own dozens of seldom-worn shirts. Resale marketplaces give preloved tees a second life, while upcycling collectives cut, stitch and reimagine worn garments into artful hybrids. A vibrant DIY ethos hearkens back to the homemade screen-printing tables of the 1960s, but with global reach: online tutorials, affordable heat presses, and drop-shipping services let anyone become their own branded-merch entrepreneur. Consumers more than ever demand transparency—full supply-chain visibility, certifications like GOTS (Global Organic Textile Standard) and Fair Trade, and corporate take-back programs that ensure end-of-life garments are recycled or composted rather than landfilled.

In parallel, marketing and branding strategies have matured. The T-shirt is no longer mere swag; it is central to “drop culture.” Teaser campaigns on social media ignite anticipation for limited-edition collaborations between streetwear labels, luxury designers and pop icons. Hypebeasts camp outside stores to claim numbered releases, transforming plain tees into coveted collectibles whose resale value can exceed ten times the original retail price. At fashion week runways, supermodels parade T-shirts bearing bold slogans—sometimes political, sometimes absurdist—echoing society’s fractious debates back into the global conversation.

Looking forward, the T-shirt’s evolution will likely accelerate through digital and smart technologies. Conductive inks and micro-sensors embedded in fabric promise shirts that monitor biometric data—heart rate, posture, temperature—and relay insights to phones or smartwatches. Phase-change materials may regulate thermal comfort, and self-cleaning nanocoatings could repel stains and odors. On-demand 3D knitting machines, already in use for shoes and bespoke knitwear, may one day spin seamless shirts perfectly shaped to wearers’ measurements, saving yards of leftover fabric and eliminating sewing waste.

Artificial intelligence will play its role too: generative design tools can conjure infinite graphic variations, optimize fit patterns for diverse body shapes, and forecast emerging color palettes by analyzing social media trends. Augmented reality fitting rooms, already appearing in retail pilot projects, allow shoppers to “try on” dozens of T-shirt styles virtually, reducing returns and making online purchasing more reliable. Blockchain and digital identity systems may authenticate rare drops, linking a physical garment to a virtual token that verifies provenance and ownership—an intersection of fashion and Web3 that some early adopters have begun exploring.

Yet for all the gadgetry and digital swagger, the heart of the T-shirt remains its democratic simplicity. It is the canvas through which political slogans gain legs, the fabric upon which subcultures sew their emblems, the unassuming top that can be both blank slate and bold statement. It is handed down from older siblings and cast off by fast-growing teens, picked up for charity runs and toss-away memorials in cemeteries, pressed into service as makeshift bandages or picnic blankets. It is slept in, stained with coffee and grass, carried home crumpled in gym bags, inscribed with memories at summer camps and war zones alike.

At the end of the day, what makes the T-shirt truly remarkable is not the cotton or the knit, the printing press or the supply chain, but the unbroken human impulse to cover ourselves with something that both protects and proclaims. From the decks of battleships to the runways of Paris, from DIY punk shows to Silicon Valley pitch rooms, this simple garment has recorded our ideals, our struggles and our triumphs. It has borne the names of our favorite bands, the faces of our heroes, the mantras of our causes—and sometimes, nothing at all, serving as the quietest form of self-expression: the unadorned, honest comfort of cloth against skin.

Two millennia ago, Romans wore tunics so basic that they look almost identical to today’s T-shirts. In that continuity, we glimpse why the T-shirt persists: it answers a fundamental human need in a form that is at once intimate and infinitely adaptable. It emerges from machines yet carries the imprint of individual choice. It can be produced in billion-unit batches yet can be hand-finished and hand-printed. It can cost a dollar in a street market or a thousand dollars in a haute couture salon. It can change every season or remain unchanged in a drawer for years, waiting for the perfect day to be worn.

So when you pull on a T-shirt tomorrow—whether it bears a slogan you believe in, a logo you admire, or a plainness you cherish—you participate in a lineage that spans millennia. You honor sailors, soldiers, musicians, activists and pioneers of textile science. You engage in a silent yet profound dialogue about who you are and who you wish to be. You wear, in cloth and color, the story of human ingenuity and expression. And in that simple act, you remind us all that sometimes the most remarkable things are the most ordinary, woven seamlessly into the fabric of our lives.